In the north there is a butte.

Even on the greyest of days the church can be seen, an illuminated

presence. To those that visit the city to admire its beauty the church

is amongst the most beloved of destinations. To others it is a symbol

of oppression and authority.

The church is an occupation built upon contested ground.

This high point in the city is a place of contradictions in the city’s

history. It is a cannon park, a gypsum quarry, a hot air balloon

launch, a graveyard, a killing field.

It is also a basilica, a holy site, a penance, a postcard.

It is here that the government, fleeing their approaching Prussian

enemy, escaped to Tours by hot air balloon. It is here that the city’s

civic guard stowed their cannons when the enemymarched triumphantly

through the streets. It is here that French soldiers ordered

to confiscate those same cannons and to use them against their

fellow citizens, turned instead upon their officers. It is here that the

first blood of the Paris Commune was spilled, as well as some of its

last. It is here that retreating Communards became entombed in the

hillside when their own army set off explosives to seal

the quarry entrances.

It is here that the victors of that conflict built a church that could

be seen throughout the city to remind the defeated of their sins.

It is here that each year millions of travelers come, drawn by the

church’s glow, to pay homage.

There are two ways to visit the church.

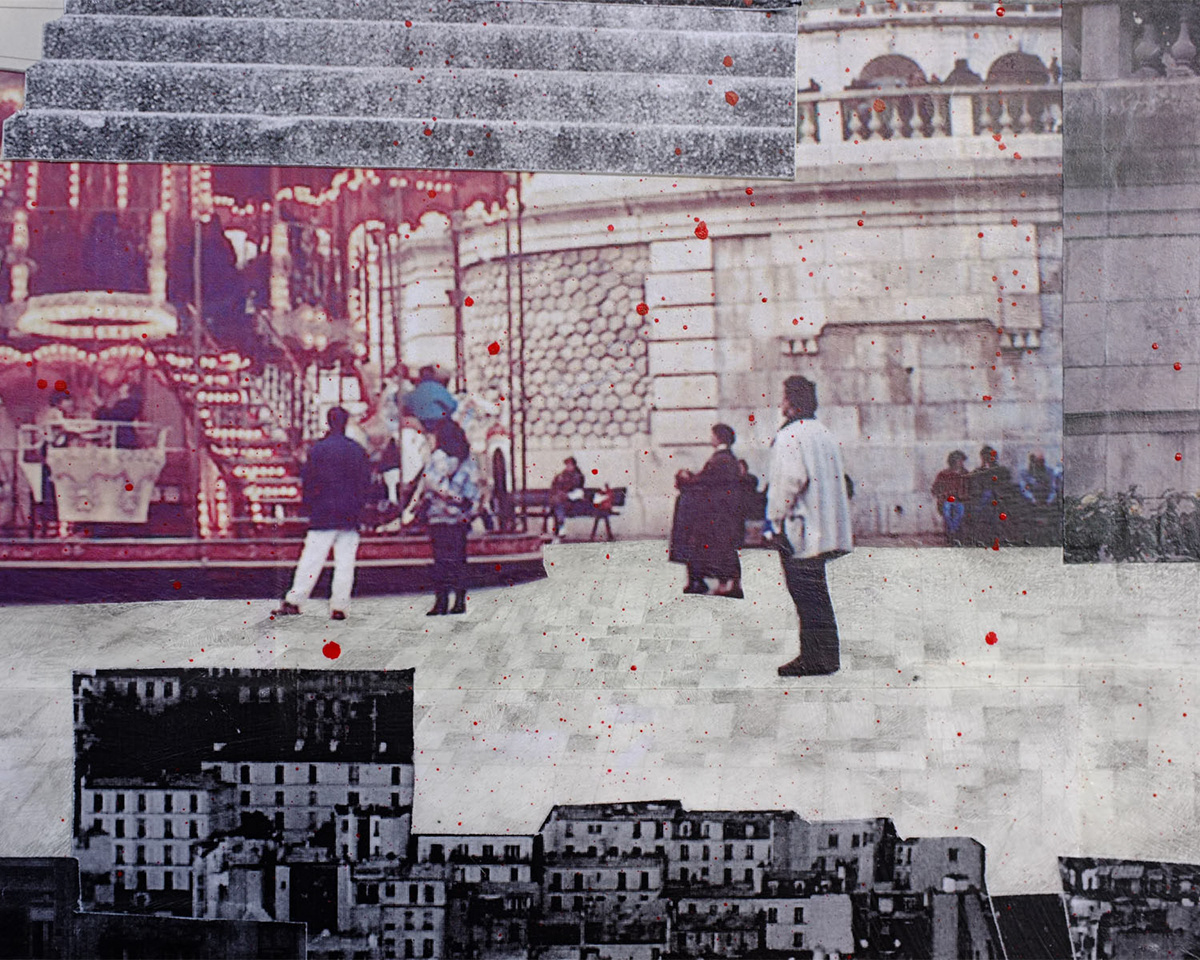

A baroque maze of staircases winds up the grassy hill that leads

to the church. On the grass the tourists laze, taking in the city laid

out in front of them. Children ride a carousel, old friends perch on

park benches like bookends and locals try to turn a profit selling

trinkets to anyone that passes.

The ascent from the square at the bottom of the hill begins with

a curved ramp that curls smoothly upwards, hugging the carousel

on one side. Upon reaching the first landing a black opening comes

into view. Between two staircases that move upward, the earth recedes

into the darkness and offers a second path. The choice is up

or down, light or darkness, the known or the unknown.

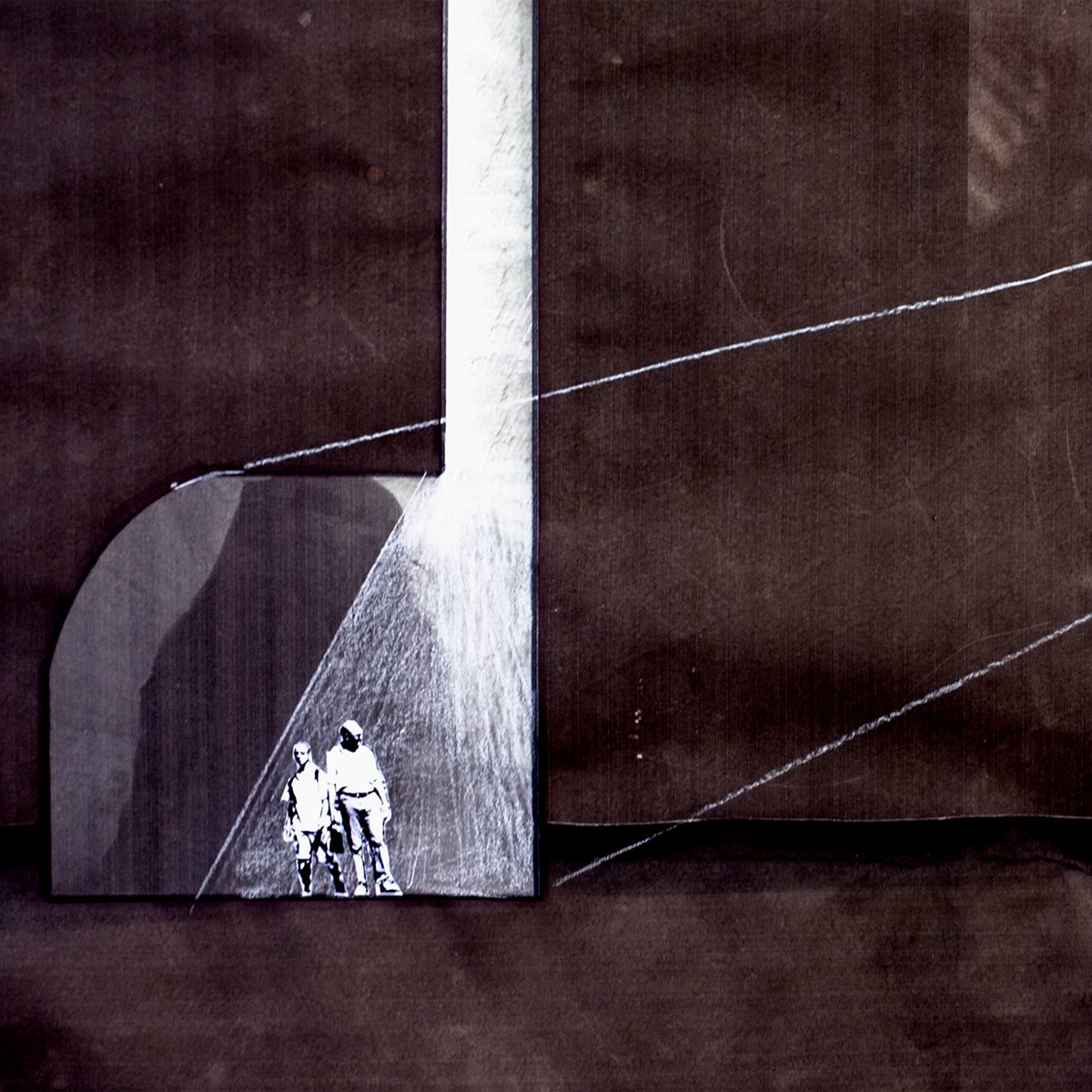

If one chooses to descend the cave becomes a ramp, which dives

into the hill. There is not a lot of light. A dim glow escapes from

the part of the tunnel where the wall meets the floor but at landings

the space is flooded with light by shafts that pierce the mass of

earth above. At each landing, the shaft is longer, and the light a little

less intense, marking the depth gained by each switchback.

Up ahead another opening becomes visible. Reaching it, one steps

out of the tunnel and into a vast cavern of magnificent, white,

rough, vaulted stone. A raised pathway that glows at it edges weaves

between these monoliths. The underground cathedral is nearly six

stories high and although the sources of light are few the stone

itself seems to be emitting a glow. The cavern is continuous on two

sides and interrupted by stonewalls on the others.

At the furthest wall, the pathway once again becomes a tunnel.

This tunnel is straight and short and consists of just one trajectory.

Upon entering one can almost make out the tunnels end through

the darkness. It shines like a beacon. Its golden

shimmer is magnetic.

Drawing closer it becomes clear the divine material makes up the

door frames of an elevator. Intelligent, they slide apart, offering

a ride to whoever moves near them. The elevator is round, gilded

gold and glass. It is impossible to distinguish whether it is new or

old. Inside there is just one button and no markings or symbols to

decipher its destination. Pressing it, the elevator gently begins to

hum. There is a brief rattle as it collects itself and then it shoots

upwards. Through the glass walls one can see the blurry layers of

earth pass by: sands and silts, marls, clays and limestone. The journey

is prolonged. This time marking with time, instead of light, the

greatness of the vertical distance traveled.

Eventually the machine slows its pace and delicately passes into a

new space. There is no outside light. The ceilings are low. Everything

is still stone but the stone has been manipulated: carved and

chiseled into arches and columns and niches and sills. The elevator

does not stop, however, it continues upwards passing great swaths

of stone and pierces the floor of the next room. Light pours in.

The first thing to come into view is a great, masonry dome and

on it the image of a man in white robes, with arms outstretched,

flanked by winged angels, kings and adoring women. A golden halo

crowns his head.